- Home

- Libby Creelman

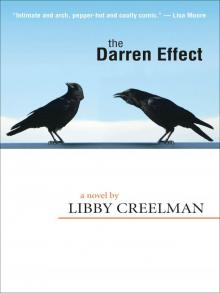

Darren Effect

Darren Effect Read online

the Darren Effect

Also by Libby Creelman

Walking in Paradise

the

Darren Effect

a novel by

LIBBY CREELMAN

Copyright © 2008 by Libby Creelman.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Bethany Gibson.

Cover photograph copyright © tiburonstudios, istock.com.

Cover and interior design by Julie Scriver.

Printed in Canada on 100% PCW paper.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Creelman, Elizabeth, 1957-

The Darren effect / Libby Creelman.

ISBN 978-0-86492-506-0

I. Title.

PS8555.R434D37 2008 C813’.6 C2007-906578-3

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP), and the New Brunswick Department of Wellness, Culture and Sport for its publishing activities.

Goose Lane Editions

Suite 330, 500 Beaverbrook Court

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

For my children, Andrew and Clara

When Benny Martin died, his wife was there, but her feelings towards him had been impossible to read for some time. There were nurses too. He sensed they were helpful, caring, nearly intimate, but he found this complicated and wished they would disappear.

Benny’s son Cooper was home asleep, dreaming a dream that would return throughout his adolescence: the two of them had caught a long iridescent fish that could both fly and swim, but resisted being reeled in to shore. It flew above the misty surface of the river, leaving in its trail colourful watery loops.

Heather Welbourne had awoken suddenly in her dark house and left her bed. Dazed, she misjudged the location of the doorway and nearly collided with the wall, but lifted a hand to protect herself at the last moment. For many years, Benny had struggled with his desire for this woman.

Darren Foley, a man Benny had never met, was in his basement tending to an injured Atlantic puffin, which would outlive Benny by an hour and nine minutes.

PART ONE

Chapter One

She went to see him in the hospital only once. As it happened the hospital staff were happy to give away information about him. It was different later when he was in the palliative care unit. But now they told her without hesitation — without even looking up from the station — that he had a private room on the fifth floor. She found it easily. She passed up and down the corridor, making sure he was alone.

She had imagined this all a number of times: entering his hospital room. He would recognize her without making eye contact, as though using a sixth sense, then turn to a statuesque nurse standing nearby in a crisp white uniform and say, Would you mind asking that woman to leave? But expecting this from him was silly. He might be angry with her, but he would not be ungracious. She would tell him it had been all her fault. It would pour out of her: she was a monster, a madwoman. She would ask his forgiveness, and at last they would talk about his prognosis. There would be a discussion of treatments, drugs, hope. What’s new with you? he would ask, and she would shrug and look away, and say, Nothing’s new. Except I’m here now and I love you. But first she would have to win him over, she would have to get him to forgive her for locking him out in the rain.

It was a Thursday morning nearing eleven thirty at the end of September. In the corridor, a trolley of lunch trays seemed to have been aimlessly placed and forgotten. The odour reminded Heather of eating as a girl at a friend’s house, where the food was always alien and a bit sickening. The nurses wore baggy salmon-coloured uniforms and did not look her way once. As she entered his room, she felt she might be floating. Her shoes made only a whisper of noise across the floor, and she moved slowly, as though the air in the room were trying to hold her back.

He was propped up in the hospital bed, looking out the window. He didn’t seem to realize anyone had entered, or if he did, he didn’t care. But as she approached him, he turned. He looked startled and then delighted. He looked at her and smiled as though he’d like to drink her in, as though all the fuss in the car had been some great lark, a game, something that only served to charge whatever was going on between them now.

But what was going on between them now? She felt wobbly. It was the anticipation and then the fact that he didn’t appear angry with her. All these weeks. She had thought he would be angry. Shouldn’t she know him better than that?

“Well. Hello,” he said. “Here you are.”

She could barely smile. She felt excruciatingly shy.

“I didn’t expect a visit from you.”

He was still smiling. Smiling as though he liked her very much. There was an obvious lack of force behind his speech and she knew she was an idiot for not having come sooner.

“I thought I might stop by. I know you didn’t want me to.”

“It’s good to see you. You don’t know how good it is to see you.”

“I’m so sorry.” She was about to cry but couldn’t do that. Someone might walk in at any moment. “I was terrible.”

“Don’t be so foolish.”

“How are you?”

“Sick. I’m pretty sick.”

He turned and glanced out the window again. There was nothing out there. Although it was a clear, bright September day, from inside the hospital the sky looked white. You couldn’t be sure it was even sky.

“I’ll be going home in a few days.”

“Really?”

“What I’ve learned. People like me. We’re in and out.”

“I better not stay. Isabella might be in.”

“Just left. You probably passed her.”

Heather shook her head. She would have noticed that: passing Isabella Martin in the corridor. She felt a familiar, fleeting bitterness.

“Don’t leave yet. You just got here. What’s new?”

“Nothing.”

“Oh, come on.” He laughed and reached for her. “Come closer. I’ve missed you so much.”

He looked the same but different, which was what she had expected. The bed was made and he was resting above the blankets in new jeans and a yellow polo shirt that made him look washed out. He hadn’t shaved yet that day, but his hair seemed to have been recently trimmed. His teeth had darkened. That was easy to see because he was smiling so widely at her. The last time she had seen him there had been the suggestion of fragility, but today was something else entirely. It caused her to ache all over.

He squeezed her hand and closed his eyes. Suddenly his face tightened.

“Are you okay?” She drew closer to him. “What is it, Benny?”

He opened his eyes and smiled at her. “It’s just so good to see you.”

Here she was. Here he was. Where she had been longing to be for weeks. Yet she found she couldn’t get a single thought to stay put in her head. Suddenly she needed to leave.

But then it was too late, the world was narrowing to include only a handful of white stars.

“Is there someplace I could sit?” she whispered. The only chair was on the other side of his bed. She wasn’t sure she would make it.

He moved his legs to make room for her on the bed. As soon as she sat, he reached for her a

nd pulled her head to his chest. He groaned softly. Her sick feeling immediately passed and the terrible coolness was followed by peaceful warmth. She never wanted to leave. It was remarkable that despite everything that had happened to him, the smell of him remained the same. In the past she had often smelled him for days after a weekend together. Despite showers and a change of clothes, and the time and distance, his smell would linger. He would seem to have left something permanent in her olfactory memory.

“I hear it’s Indian summer out there.”

She nodded. “It’s hot.” His legs looked like poles.

“How come you’re not in shorts?” He shook her weakly. “Or a dress? Uh? Where’s that one we bought? What do you call that pattern? That floral thing?”

“Paisley.” She felt a twinge of impatience. He always asked that. He seemed to be determined to forget the word. “I called your house,” she told him.

He sighed. “I know, Heather.”

“I shouldn’t have.”

He let out a long breath. The calling was not important. Not at this point and because she had nothing to do with his house and home anyway. Only a fool would entertain hope now — for a genuine public life with this man but also, she saw, for his recovery. She sensed a new frontier between them. She wanted to stroke his hair, run her hand across his chest and into the hard dip at its centre, but it wasn’t her territory. She couldn’t move. She would hate herself for this later. She felt she had become desensitized to the world around her. She felt a terrifying, soft floating.

“I’m going to miss you so much,” he said.

She couldn’t find the right words. She pressed her face into his chest, but all she felt was the fabric of his yellow shirt. She lifted her face and pressed it against his.

He had a way of saying goodbye, on the phone, in the car, on the sidewalk, that day at the hospital, that was soft and unmanly. His way of uttering those two syllables had always surprised her. It seemed to signal an exceptionally sad parting, even though there had never been a reason to be this sad before.

She had thought, so this is goodbye, before. But this, this was goodbye.

Outside the hospital she stood bewildered, unable to make a decision and move in any one direction. There was her office, but it was Saturday. She could go home, but she would only think of his visits, slipping in the back door, often unexpectedly, never knocking. Everything around her — people irritated by her blocking them on the sidewalk, the shimmering cars, the sky, all that baking concrete, even the parking meters — was coming at her in waves, beating at her face and hands and urging her to an action she couldn’t fully imagine. She had left him sitting on the edge of his bed, dejected, alone, brave, pale, watching her as she backed out into the horrible smelling corridor. If she were a different woman she would muscle in on Isabella Martin. She would insist on some right to participate. To spend hours in that hospital room. Hold his hand, kiss his brow. To care for him, too.

But was that something he wished for?

How was she going to get through the next few weeks and months, the rest of this insane, unseasonably hot day? The weather reminding her of meeting him in Spruce Cove six years ago.

That day had been record-breaking in its heat. Early June and hot, even in the morning. She’d been the first awake and strolled down to the beach alone. She was wearing long pants and a turtleneck, and told herself repeatedly to return to the cabin she was sharing with her sister to change into something cooler. But the ocean drew her away from the cluster of cabins that lay in the field behind the parking lot and beach. She was admiring the blue-grey humps of hills that armed the bay, so far away they had looked soft as paint, and beyond them, the white clouds that blurred the meeting of sky and sea. Everything — the water, sky, hills — seemed to speak of heat.

The dog had appeared out of nowhere, barrelling across the sand with a speed that paralyzed her. A dripping wet black Labrador retriever. Its name was Inky, she would later learn, in the prime of its short dog’s life. It stopped two feet from her and flopped back ungracefully on its haunches. Its curiously housed penis, she saw, was grainy with sand; its expression, fierce and brutish. Lowering its nose to the sand, it released a salivaencased tennis ball at her feet, then looked up at her, its ears soft tents rising, and nudged the ball closer until it touched her toe.

Then it began to bark. It rose — barking — front legs splayed as though it might pounce — barking, looking her straight in the eye. Heather wondered if it were rabid. She tried turning away from it, to snub it, to savour the view again. But the barking would wake everyone in the cabins, certainly everyone in the campers at the edge of the parking lot. She remembered hating that dog. Imagine, hating Inky — a creature perpetually cheerful, agreeable, loyal.

Now, as she crossed the hospital parking lot, she smiled, thinking how terrorized she had been. The smile felt good on her face, then sparked a terrible moment of clarity — she was no longer on that beach but outside this hospital, minute by minute increasing the distance between herself and a man whose dying seemed incomprehensible.

She had walked away from the dog and beach — not quite tiptoeing. When she looked back, she saw it hadn’t moved, not even followed her with its eyes. But it was still barking and it was the barking she wanted to escape. She stepped off the sand and across the small lot where several cars had parked in no discernible pattern. She made her way to a minivan and moved behind it, blocking her view of the sea and the dog, and realized the level of her distress. I’m such a coward, she thought, closing her eyes and leaning against the warm metal of the van, but just let that demented dog run off and persecute someone else. This was what she had been thinking when she opened her eyes and found him standing just feet away, watching her.

She assumed he was a tourist. Ontario, possibly the New England states. But when he spoke, she knew he was from St. John’s.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

Not, she would later tease him, Can I help you? Are you all right?

“Hiding from a horrible dog.” He was short and athletic looking. She noticed his hair was untidy and flying off, though there was no breeze at all. It might not have been combed in days.

He laughed. “You’re not referring to Inky?”

She realized the barking had stopped just as the dog came trotting around the side of the van. It was covered in sand and panting.

“Where’s your ball?” the man asked the dog in a calm, business-like voice. The dog stopped and looked at the man. It retracted its tongue and with some difficulty closed its mouth around it. Heather watched its head swing left, right, left. Then it did two complete turns and looked again at the man.

“Where’s your ball?” he repeated, this time, it seemed, more intimately.

The dog sprinted back down to the water and Heather made a move to go. She could feel the sweat collecting beneath her breasts along the underwire.

“By the time he’s finished rolling on top of that ball, he’s forgotten it exists,” the man explained.

Heather tried to appreciate the remark. She had no interest in dogs.

“Camping?” he asked.

“No, no. We’re here for a writers’ retreat.”

“You’re a writer, are you?”

She hesitated. She was warmed by his voice, his confidence and easy curiosity about her.

“Yes, we’re staying in the cabins,” she said. “For the weekend.”

A week later when they met again at the lecture, she was forced to tell him she was not a writer. She was a social worker, tagging along after her younger sister, Mandy, who was the aspiring writer.

He moved towards the van and leaned against it, letting her know it was his. He was looking at her, thinking something about her, and although she would have liked to have known what, her instinct was to offer him nothing more, and to ask him nothing about himself.

She had said goodbye abruptly and walked away from the man with his van and dog and returned to her cabin.

At first she thought nothing more of him. There was an afternoon poetry workshop out in the field, under the few trees and in the face of some welcome, unpredictable sea breezes. Before the readings could begin there was competition over the shadiest spots to sit, then argument about someone’s suggestion they delay supper in order to avoid the hot kitchen, but eventually they all sat back, fanning themselves with their manuscripts.

Heather stared at each face without listening. It wasn’t until she lay flat on the grass and looked up at the sky and tried to focus on the one misshapen cloud that she realized her distraction was formidable, uplifting and irresistible. She spent the remainder of the weekend returning every hour or so to the beach, but the man, dog and minivan had vanished. She nursed a small fantasy: reliving the meeting, rewriting the conversation. His expression. Her appearance. She emitted confidence, she spoke to the dog and even stroked its bony forehead and soft creased ears. She wasn’t sweating and the man asked her what her plans were for the rest of the day.

It was a public lecture held on campus. Had she known anything about him, she would have known he was married and, surely, she would have avoided eye contact, pretended she could either not remember him at all, or not remember where she’d met him. But she did not know anything about him and she went straight up to him. He stood by the table with the books and refreshments and he waited for her, watching her approach — only a few seconds, really — and when they started talking they could have been talking about anything under the sun. When he asked if she’d like to go for a drink after the lecture, she wasn’t even relieved. She knew then who he was — not his name or what he did, but what he would come to mean to her — and she knew that he knew.

His name was Benny.

It was a fluke either of them had been there. Later, Benny would call it fate, though only half seriously. It was the last in a series of public lectures for the year — that night on outport architecture. Benny had felt obliged to attend. Heather was there to meet Mandy and Mandy’s partner Bill, a university professor, but they didn’t arrive. Heather suspected they had quarrelled, but she never asked.

Darren Effect

Darren Effect